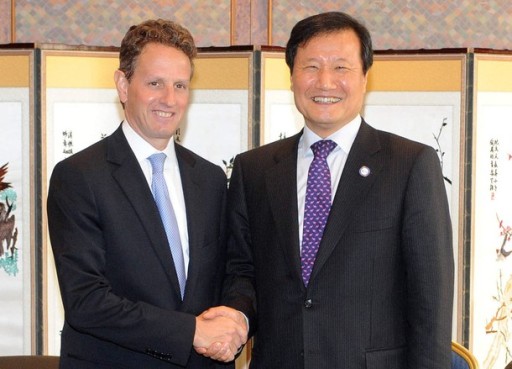

- South Korean Finance Minister Yoon Jeung-hyun (R) shakes hands with U.S. Treasury Secretary Timothy Geithner during a meeting ahead of the G20 Finance Ministers and Central Bank Governors meeting in Gyeongju, southeast of Seoul, October 22, 2010. G20 officials are unlikely to reach an accord rejecting currency devaluations and capping current account balances, an informed source said on Thursday, after U.S. proposals ran into stiff opposition. (GETTY IMAGES / REUTERS/Finance Ministry/Handout )

October 22, 2010 (KATAKAMI / BBC) --- Finance ministers from the G20 leading economies are meeting in Gyeongju, South Korea, ahead of a summit by heads of state and government next month.

Continuing tensions over exchange rates are likely to dominate proceedings.

China is resisting pressure to allow the yuan to appreciate significantly, and many developing countries also fear a currency rise could hit exports.

Low interest rates in wealthy countries have encouraged investors to seek better returns in emerging economies.

Common approach

The G20 is trying to find a co-ordinated path out of the financial crisis.

All the signs are that the finance ministers will struggle to make significant headway.

Many developing countries are concerned about upward pressure on their currencies, which could make their exports less competitive.

Behind that pressure are very low interest rates in rich countries, which have led investors to seek better returns in emerging economies. That tends to push the currencies higher.

China has resisted this upward pressure on the yuan by buying dollars.

There is a widespread desire in the G20 to see China cut back on currency intervention

There is a widespread desire in the G20 to see China cut back on the intervention and allow the yuan to rise, expressed most forcefully by US officials.

But China shows no inclination to make much of a move in the near future.

The other factor behind the currency tension - the low interest rates in rich countries - is also unlikely to change soon.

It is a result of their faltering economic recoveries.

Indeed, there are signs that central banks in the US and UK might take further steps to simulate recovery, which could lead to still lower interest rates and even more money flooding into emerging economies, further aggravating the currency tension.